Are there gender differences in the number of research proposals submitted?

By Torger Möller (German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW), Berlin)

Posted on August 08th 2023

A common finding on gender disparities in research funding is that there are no gender differences in grant success rates, but differences in application behaviour. Rissler et al. wrote that “women are as likely to be funded as men, but the percentage of women submitting proposals was less than expected” (Rissler et al. 2020, 814). Almost a decade earlier, Ranga, Gupta, and Etzkowitz (2012) came to a similar conclusion in their review on gender aspects in research funding: “Significant gender differences exist in grant application behaviour (…), but not in the male or female faculty success in acquiring grant funding” (Ranga, Gupta, and Etzkowitz 2012, 18).

The conclusion that women submit fewer grant applications than men is demanding and not easy to determine. In 2009, the European Commission had pointed out that “most funding organisations do not monitor the pool of potential applicants by gender. Much more attention should be paid to this point” (Commission 2009, 71). Little has changed in this situation to date. Research funding agencies know a lot about their applicants, but little about the pool of potential applicants.

A common approach to study gender differences in application behaviour is to compare the gender ratios of applicants and potential applicants. For potential applicants, data from national statistical offices can be used to provide information on the number of academics by gender and discipline. But comparing data from different sources involves several challenges. For instance, research funding programmes cannot easily be assigned to individual disciplines or a group of disciplines. Research fields could be part of a discipline or transcend the traditional disciplinary boundaries. Moreover, the data from statistical offices are not based on disciplinary research practices but often on employment relationships in departments. For example, not only medical academics work in medical departments, but also biologists, biochemists, epidemiologists, psychologists, sociologists, and others. Thus, comparing the gender ratio of applicants in a cardiology research programme with the gender ratio in medical departments bears various sources of distortions and errors.

The above problems can be avoided by collecting the grant application activity directly from academics as potential applicants. That is the path we have taken. In cooperation with the DZHW Scientist Survey (Ambrasat and Heger 2020) we have asked academics at German universities about their grant application behavior. The DZHW Scientist Survey is a representative survey that has been conducted regularly since 2010. The following analysis refers to the latest survey from 2019 and includes 8,198 completed questionnaires after data cleaning for our purposes.

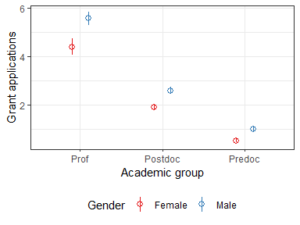

We asked researchers at German universities how many funding applications they had submitted to external funding bodies in the last five years (2015-2019). All applications with a volume of more than € 25,000 should be indicated, regardless of whether they are approved, rejected or still undecided. Figure 1 shows the average number of grant applications and its 95% confidence interval differentiated by academic group and gender.

There are significant (no overlaps between the confidence intervals) and expected differences in application activity between the academic groups. Professors have submitted on average more applications in the last five years than postdocs and predocs. Whether postdocs and predocs only collaborated on proposals or submitted some themselves as principal investigators cannot be conclusively clarified based on the survey data. Some German funding agencies do not allow researchers to submit their own proposals until they have completed their doctorate. Furthermore, there are also funding lines in which even professors are not eligible to apply, but only research organizations, e.g. in the German Excellence Initiative / Strategy.

Figure 1 shows that there are not only significant differences between the academic groups, but also between gender. Men submit more applications on average than women in each academic group. Could we conclude that there is an overall gender difference in applying for grants? This conclusion seems to be reasonable, but an analysis of the same data differentiated by research fields yields a contrary result.

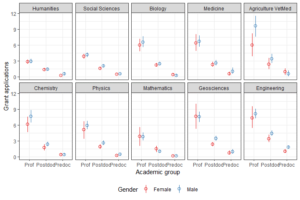

Figure 2 shows that the significant differences between the academic groups persist within research fields. The highest application activity is among professors, followed by postdocs and finally predocs, but the obvious gender differences in application activity presented in Figure 1 are either diminishing or reversing. By comparing the average number of grant applications by gender for ten research fields in three academic groups we have thirty comparisons. In most cases, men submit more applications than women, but in seven cases women are ahead of men. The overall application differences are small, and the question is, are they statistically significant. We get a quick answer by comparing the confidence intervals shown in Figure 2. Robust results based on negative binomial regression analyses are published in Möller (2023). The findings reveal that the significant gender differences disappear when controlling for the research field.

The same data indicate, on the one hand, that female academics submit on average significant less grant applications than men (Figure 1), but on the other hand the significant difference disappear after taking the research field into account. Is this a paradox? Yes, and it has a name. The Simpson’s paradox (see Sprenger and Weinberger 2021) is a statistical phenomenon where an association between variables, here number of applications and gender, disappear or reverse when the data set is divided into subgroups, here the fields of research.

How can these different results be explained? The proportions of women and men at German universities and in the various research fields are not equal. At the time of the survey (2019), 43.1% of predocs and postdocs were women (Destatis 2020). Among professors, only 25.6% were female, and among the higher grades (comparable to full professor) only 21.2%. These different gender shares are also reflected in our survey data. Let’s take the group of professors: The proportion of women differs considerably between research fields. It is higher in the humanities and social sciences and lower in engineering, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and geosciences. As we can see in Figure 2, application activity in the humanities and social sciences is lower than in other research fields, except mathematics. Female academics are overrepresented in fields where the number of grant applications is lower. Therefore, the overall average application rate of women is lower than that of men, as shown in Figure 1.

The application activity has mainly to do with resource needs and not with gender. We have asked the academics how much external funding they need for conducting their research. In the humanities and social sciences (and mathematics), less external funding is needed than in engineering, natural sciences, and life sciences. In short, some only need a computer for writing, a desk, and a library, while others also need a laboratory, measuring instruments, chemical, biological, or physical material and a mainframe computer for calculations. The demand for resources is directly related to research practice, but not to gender. Men do not submit more grant applications because they are men, but because they work in research fields that require more resources, which leads to a higher application rate regardless of gender.

In this respect, the answer to the question of whether there are gender differences in the number of research proposals submitted: No, female academics submit as many grant proposals as their male colleagues in the same research field.

References:

Ambrasat, Jens, and Christophe Heger. 2020. Barometer für die Wissenschaft. Ergebnisse der Wissenschaftsbefragung. Berlin: Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung (DZHW). https://www.wb.dzhw.eu/downloads/wibef_barometer2020.pdf.

Commission, European. 2009. The Gender Challenge in Research Funding: Assessing the European National Scenes. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/36195.

Destatis. 2020. Bildung und Kultur. Nichtmonetäre hochschulstatistische Kennzahlen. Fachserie 11 Reihe 4.3.1. Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DEHeft_mods_00137319.

Möller, Torger. 2023. Do female academics submit fewer grant applications than men? 27th International Conference on Science, Technology, and Innovation Indicators (STI 2023). https://doi.org/10.55835/644303d4b2b5580ba561581a.

Ranga, Marina, Namrata Gupta, and Henry Etzkowitz. 2012. Gender Effects in Research Funding. A Review of the Scientific Discussion on the Gender-Specific Aspects of the Evaluation of Funding Proposals and the Awarding of Funding. Bonn: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. https://www.dfg.de/download/pdf/dfg_im_profil/geschaeftsstelle/publikationen/studien/studie_gender_effects.pdf.

Rissler, Leslie J., Katherine L Hale, Nina R Joffe, and Nicholas M Caruso. 2020. Gender Differences in Grant Submissions Across Science and Engineering Fields at the NSF. BioScience 70 (9): 814–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaa072.

Sprenger, Jan, and Naftali Weinberger. 2021. Simpson’s Paradox. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/paradox-simpson/